May 1972, is the month that changed the course of Cameroon’s history and sent it on a downward spiral towards imminent catastrophe.

May 20th, 1972, is the day that placed a knife on the tiny cords that held the country together in what was known as a Two-State Federation, thereby putting into peril, the precarious unity forged in 1961.

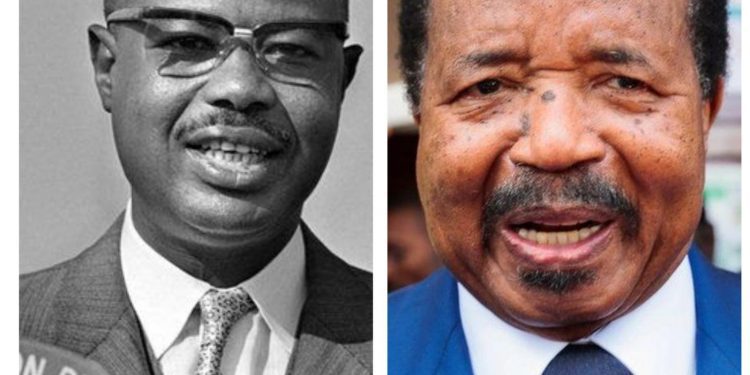

This is the month and date during which the country’s erstwhile President, Ahmadou Ahidjo, changed the form of state from a federal one to a unitary one. This, he did, through a referendum that recorded a 99% ‘yes’ vote.

While the referendum itself was unconstitutional, that was beside the point. The fact that the ‘No/Non’ ballot papers were not seen at many polling stations, made it a democratic farce rather than a referendum.

At that time, few appeared to express dissent, probably out of fear rather than admiration for the decision.

Ahidjo was known to be repressive in all extremes, and any moves to kick against his wish were going to be synonymous with suicide.

It signified to many Anglophones, the start of the end to all they ever knew as culture, language, education, legal system, freedom of expression, leadership, and of course, lack of excessive administrative bottlenecks.

The supposed national unity was, to them, the birth of more repression. It was much like a change of status of servitude under the British slave-masters to one under abusive fellow Africans.

The name of the country changed from the Federal Republic of Cameroon to the United Republic of Cameroon. The flag itself suddenly lost one of its stars, signalling the disappearance of one of the two states.

Ten years later, in 1982, the cracks in the system were already evident. Attempts to unite East Cameroon and West Cameroon needed more than just a coat of paint.

It needed concerted action and practical application of situations, all ingredients Ahidjo had failed to mix in the soup. It was more of an attempt to assimilate the Anglophones and make them French Cameroonians, a move President Biya later admitted, had failed woefully.

For a start, many had thought Biya would change the course, given that he had long served in the Ahidjo regime and was abreast of the state’s unification challenges.

Paul Biya, however, toed the line, and the system kept functioning as usual until his boat nearly capsized. While the 1984 attempted coup was judged a move by Ahidjo to regain power, it also further worsened the cracks in the once patched national unity.

It became more evident that the state was being run on ethnic and interest lines rather than on the course of the common good.

Within this time, the campaign for a return to federation was fast rising, as were those clamouring for a return to the pre-1961 boundaries of two separate Cameroons.

Yet, both met with repression and denial of the existence of any problem. Paul Biya threw fuel into the seething flames by renaming the country ‘The Republic of Cameroon’, with the elimination of the cosmetic word ‘United’.

This, according to many commentators, signalled the final act to erase the Anglophone identity.

In 2004, President Paul Biya attempted to appease the dissenting voices, as the pressure of multiparty politics had made the mix harder to control. Thus came the birth of decentralisation.

Cameroon’s Constitutional Law of 18 January 18, 1996, enshrined decentralisation as a fundamental principle of the organisation of state governance. It was meant to affirm the central government’s commitment to transferring a number of powers to local authorities with a view to local management.

However, many argue that it was not until 2004 that real traces of decentralisation were witnessed in a few sectors of public life. The new law, among others, saw the introduction of legal instruments of application to effectively accelerate the pace of the decentralisation process and good governance.

Yet the much-heralded initiative became another white elephant project. The actors and beneficiaries of devolved powers had limited capabilities, local authorities faced financial constraints, and endemic corruption made it difficult.

The elephant in the room

For over ten years, the Biya regime still could not solve the puzzle. What followed, however, was more societal ills, including a failed judicial system, topping the charts on global corruption indexes and excelling at arresting and torturing pressmen.

The 2008 public uprising was not handled any better. To date, many arrests remain unaccounted for.

Yet, the failures of the decentralised government and the violent crackdowns were just preparing Cameroonians for something bigger and worse—the Anglophone crisis.

From inception, it appeared to be just another ‘pocket of resistance’ that would be squashed in a day or two. But then, it grew bigger, and today, it gains more attention than even the Boko Haram armed conflict.

This time, it was not just a particular sector protesting. It was an entire people who once had a distinct identity.

It was a unified people with one voice saying, “Enough is enough”. Lawyers, teachers, and civil society leaders stood hand in hand, nearly bringing the government to its knees.

Pro-independence campaigners then seized the opportunity to advance their agenda, becoming violent in the process.

While the timeline of the conflict itself is a whole tale, one of the most remarkable moments came on September 10, 2019, when President Biya broke the silence.

He announced the holding of a Major National Dialogue. The event was meant to address multiple issues plaguing the country, including the ‘Anglophone Problem’ that had, hitherto, never been a problem.

Many people initially welcomed it, but then a few people voiced their concerns. First, separatist leaders who were in jail were not to be part of it. As if to add salt to injury, the form of state was not to be discussed.

Diaspora actors too were not a part of it, as many cited the lack of guarantee of their freedom as well as the fact that Cameroon was no longer a neutral venue.

The likes of Battonier and former presidential candidate, Akere Muna walked out. His brother, late Ben Muna, it should be recalled, had ignited a similar fire in the early years of the crisis when he said the youths should “bloody fight” if that’s what it takes for them to have a future.

Learned nothing and forgotten nothing

The strings holding so-called national unity intact continue to give way. Many have described the resolutions of the process as a glorification of the decentralisation process, which is still not in full force.

A house of chiefs, a regional assembly, and more powers given to local administrators. Yet, the form of state continues to revolve around Yaounde and a few leaders who appear to have lost touch with reality.

Without much to show for it, regime songbirds continue to chirp about national unity. For 50 years of a unitary system, the most remarkable landmarks remain contested election results, sloganeering, widespread corruption, and, of course, arbitrary arrests and detention.

President Biya said in January 2019: “My wish is that, eventually, national unity will be strengthened.”

Like many other wishes of the ruling class, what ordinary Cameroonians have seen is more repression and financial exploitation. Truly, wishes are not horses. Not for Cameroonians, and certainly not for their ruling class.

The regime has relied greatly on the oppressive armed forces to stay in place throughout these tumultuous 50 years. It is therefore little or no surprise that National Unity Day revolves a lot around them.

With their input and the government’s impressive public relations campaigns showing the world all is well, one would hardly take seriously the dissenting voices and pleas of the oppressed.

But if gold can succumb to the power of rust, so too can loyalty that is abused. The forces are like every other Cameroonian, human first, with a conscious and moral rectitude to do the right thing. What then will become of the much-heralded national unity when they, too, like Anglophone lawyers, teachers, civil societies, and communities in 2017, raise their fists to the sky to say it is time to put the country first?

Will the loose threads of the 1972 referendum contain that too, or will slogans and verbal national unity do the trick this time?

Today, the Anglophone crisis persists, and the root causes remain unsolved. Yet, the nation sings a national unity song and fetes the very armed forces wreaking havoc, maiming, torturing, and, in most instances, killing their own countrymen. To many Anglophones, the day today will represent nothing less than more memories of playing second fiddle. This is a status they were born into, and they may leave God’s green earth without ever seeing a change.

In all this, however, the question that remains answered is: how can Cameroon continue to celebrate a National Day of Unity, on a day that poured scorn on its constitution; set the country on the path to destruction, and remain the source of discontent across large sections of the country?