By Tata Mbunwe

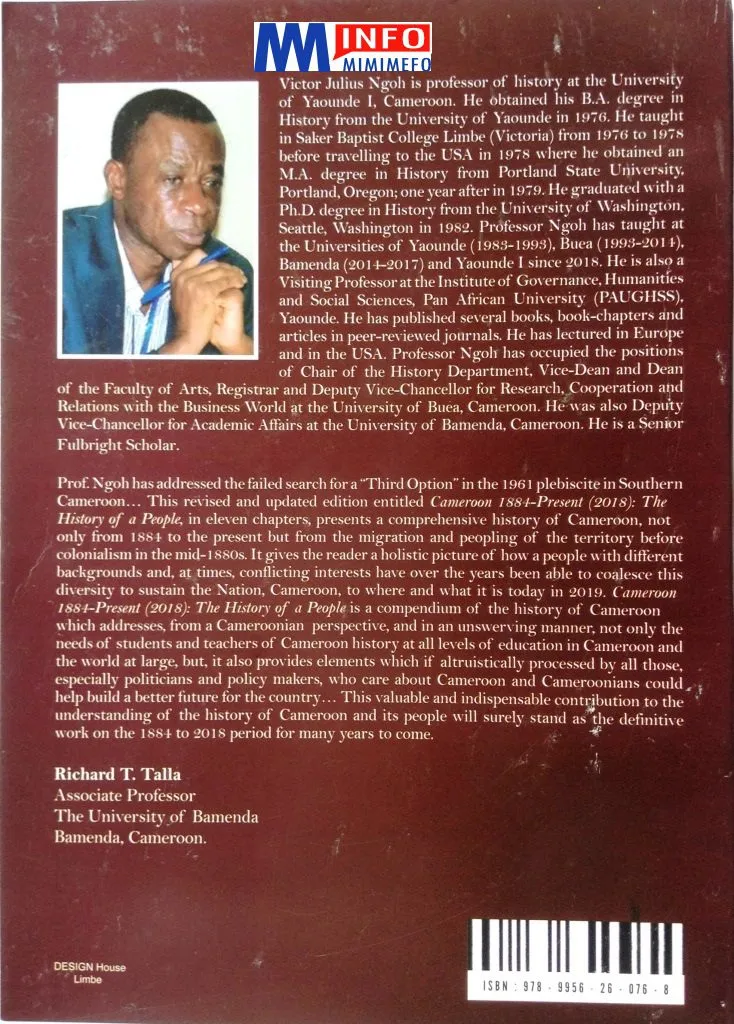

Four years into the crisis in Cameroon’s two English-speaking regions, the country’s renowned historian and writer, Prof. Victor Julius Ngoh, has countered conceptions that the marginalisation is the problem causing the crisis.

He said the problem is rather the failure of the Cameroon Government to keep the terms of a 1961 reunification between the majority French Cameroon the smaller English-speaking Cameroon.

Prof Ngoh, who is President of the Catholic University Institute of Buea (CUIB), was speaking to MMI in an exclusive interview in Buea recently on the heels of October 1, a day on which separatists in the English-speaking regions commemorate the secession of the two regions.

They declared independence in 2017 and pronounced the birth of the “Republic of Ambazonia”, the name of the breakaway state.

Their principal argument has been the marginalisation of the English-speaking population by the majority French-speaking government. Marginalisation is also believed to be the main cause of a lawyers and teachers strike in 2016, which formed the birth of the current armed conflict.

However, Prof. Ngoh, who has published elaborately on Cameroon history, argues that what is referred to as Anglophone marginalisation is just a consequence of the failure by both governments of former President Ahmadou Ahidjo and President Paul Biya to maintain the Anglo-Saxon system as agreed during reunification in 1961.

He said the 1961 Foumban constitution preserved both the English and French cultures but successively, the Foumban agreement has not been respected by Cameroon’s two successive Presidents.

He said the failure to preserve the Anglo-Saxon system, as agreed in Foumban, is the problem that has manifested itself through marginalisation and the on-going armed conflict.

“The Anglophone Problem is not a problem of marginalisation as such. It is not the problem of Anglophones not being appointed Secretary-General at the Presidency or being appointed Minister of Finance or Minister of Defence or Minister of External Relations, or be appointed General-Manager of SONARA, that’s not the problem.

“If for example an Anglophone is appointed Minister of Defence, how will that solve the Anglophone problem? The appointment of an Anglophone as Minister of Territorial Administration, how has that solved the Anglophone problem? The appointment of an Anglophone as Minister of Secondary Education, has that solved the problem? Those are the manifestations of the problem, the consequences and not the problem,”

Prof Ngoh said during the interview.

“The Anglophone Crisis is the result of the Anglophone problem: the inability of the successive governments of Cameroon – the Ahidjo and Biya governments – to adequately implement what John Ngu Foncha and Ahmadou Ahidjo expressively stated at the Foumban Conference in July 1961.

“Summarily, they agreed that the Anglo-Saxon system in Southern Cameroons will be maintained and allowed to flourish as it was in Southern Cameroon, while the French system will be allowed to flourish in the Republic of Cameroon.

“It was on this basis of a federation that reunification was subsequently implemented from October 1961. Unfortunately, between 1961 and 1972, a series of social, political and economic policies were implemented by the Ahidjo government which did not adequately respect what was agreed at Foumban.

“This was made possible by the internal political differences within West Cameroon and by the smart political know-how of Ahmadou Ahidjo who exploited the differences in West Cameroon. And also the coming into being of a de facto one-party system in West Cameroon did not favour a federal system which was finally abrogated in 1972.

“This abrogation now brought to the forefront the differences which the English-speaking population of former West Cameroon experience, and this was aided by the demographic advantage that East Cameroon had with regards to West Cameroon.

“Then came 1984 when President Paul Biya, through the National Assembly, changed the name, United Republic of Cameroon, to simply the Republic of Cameroon, which was the name former French Cameroon adopted at independence on January 1, 1960. To most Anglophone activists, it gave the impression, rightly or wrongly, that the former French Cameroon has assimilated, or annexed the former West Cameroon.

“So, the change of name made a good percentage of Anglophones to believe former Southern Cameroons has been assimilated; have been annexed. And this aggravated the Anglophone problem. More so, when it became evident that almost everything was in French: Presidential Decrees, Presidential and Ministerial orders were in French, almost all official pronouncements by the President were in French and this did not speak well as far as the English-speaking population is concerned and more and more, the Anglo-Saxon educational system became swamped by the French educational system and the Anglophones felt that they did not have a voice.

“In addition to that, we have the legal system; the judicial system; the Common Law system and the Anglophones did not find themselves in the new political set up. What happened in November 2016 was just an outburst of the frustrations that Anglophones experienced.”

“Restoration” of Independence

According to Prof. Ngoh, English-speaking Cameroon did not gain independence before reunifying with the already-independent French Cameroon. Rather, the later gained independence by joining the former.

“There is a misconception that Southern Cameroons achieved independence before reunification. Southern Cameroons never achieved independence before reunification. The UN Resolution 1608 of 21 April 1961 said the termination of the trusteeship agreement will be effected midnight 30 of September 1961 upon Southern Cameroons joining the Republic of Cameroon.

“It never said Southern Cameroons had independence. So, this concept of ‘We want our restoration of independence’ is wrong and misleading and unfortunately young Cameroonians have been killed in this crisis with the misconception that they were fighting for the restoration of their independence. What makes me annoyed at times is that the political history of Cameroon has been put in the mud so much so that anybody believes that he or she is a historian…,”

he said.

He said the crisis in the two regions, which was first started by disgruntled Anglophone lawyers and teachers on the basis of marginalisation, only aggravated because an ‘uninformed’ population was allowed to usurp the movement.

“The biggest mistake that the Anglophone lawyers and teachers made was that they invited all the “buyam sellams” and masses to join them. It was an uneducated mass, an ill-informed mass who just followed and eventually took over the movement. The teachers and lawyers no longer had control. The teachers and lawyers called for the boycott of classes but if you are honest enough you will accept that at the end of the day, it is still going on a good number of teachers have been killed, kidnapped; school children have been killed; whereas they are the ones who planned the boycott and the strike. So, they allowed the masses to join them and take over and this was also aggravated by the refusal of Cameroonians in the diaspora to have the population of Anglophone Cameroonians at heart. To be frank the government also minimised the crisis; the government thought the problem could just be solved by organising a few meetings and settling those who will attend the meetings with perhaps their lodging fee. But that was not the case.”

The Professor also lauded calls for school resumption by many separatist leaders and activists who have been advocating school boycott in the past four years and in many cases, vandalising students, teachers and education infrastructures.

The historian said education, which is basic necessity, should not be held at stake in a political struggle.

“The way forward is education. The education boycott that the separatist fighters called for is about 80 per cent ineffective. School boycott has only affected the poor masses in the rural areas who cannot send their children elsewhere to school.

“We can see that Anglophones have opened schools in the Francophone regions and Anglophone students are enrolling into them. We can see that Schools have been going on in all major Anglophones cities for the past four years and Anglophones who could afford have also sent their children to Anglo-Saxon schools in the Francophone regions. In fact, those who are calling for school boycott are sending their own children to school abroad while preventing the poor villagers from sending children to school.

“However, is actually positive seeing that most of the separatist leaders calling for school boycott have realised the necessity of education and are now calling for school resumption. I pray that the government should join hands and put in place what is necessary for effective school resumption. But you cannot say schools should resume but uniforms should not be worn. And we understand the wearing of uniforms is one of the key aspects that characterise the Anglophones sub-system of education from nursery to secondary school.

“If you say schools should go on but French should not be taught in school you are indirectly saying all Anglophones who teach French should remain jobless and unemployed. I must say that Cameroonians do not know their history, that is why government should make history compulsory from primary level to the university. There are many ways through which this can be done, maybe by introducing something like history 101 in the university for example, however it may be done, which all students, whether they are studying chemistry, law, biology, are bound to take.”